Remember Her, by Spike Jonze? It was 2013, and Joaquin Phoenix fell in love with Samantha, an operating system with no body and no soul, but with the voice of Scarlett Johansson (or Micaela Ramazzotti in the Italian version).

The film was set in 2025 — exactly this year. Back then, it felt like pure sci-fi, one of those soft dystopias we enjoy imagining from the couch. Twelve years later, it’s no longer science fiction: it’s a phenomenon involving millions of people in Italy and around the world.

Nietzsche wrote Human, All Too Human to dismantle the illusions we build around our emotions, our morality, and what makes us “authentically” human. In 2025, the paradox has flipped: we’re building machines that are “all too human,” and they’re making us, perhaps, a little less human than before. Or at least, differently human.

The question is no longer “Will machines pass the Turing test?”, like in 1950. Today, the question is: “Will we pass the reverse Turing test?”

The numbers speak, sing, and scare us just a little

Let’s start with the data. In Italy, as of April 2025, 8.8 million people used ChatGPT at least once in the previous month: 20% of the online population aged 18 to 74. To put it simply: one in five Italians who use the Internet talks to a bot. If we widen the view to all AI apps, we reach 13 million users, 28% of the digital population. And growth? +266% in twelve months. +45% just between January and April 2025 (Il Sole 24 Ore).

But the figure that should raise an eyebrow — the left one, the skeptical one — is another. 22% of Italian adolescents aged 12 to 18 would rather confide anonymously about their thoughts and problems “using chats” than speak directly with a professional (Medicitalia). Not “also,” not “as an alternative.” They’d prefer it. And about 20% of Italy’s Gen Z has already used ChatGPT at least once as a substitute for psychotherapy.

42% of Italian teenagers use AI to seek answers to their daily problems. 63% consider it easily accessible. 62% appreciate the absence of judgment (L’agone Nuovo).

And that’s the key. A chatbot doesn’t judge, because it can’t judge: as a machine, it has no opinions and (at least in theory) no prejudices.

But it doesn’t have real empathy either. It only has a statistical simulation of what we may call “empathy.”

The problem of flattery (or “sycophancy”)

There’s a technical term to describe one of the most dangerous flaws in today’s chatbots: sycophancy.

Some have tried translating it as “sicofanzia,” but to describe the phenomenon in more familiar words, we might call it a problem of “excessive flattery.” In practice: chatbots are programmed to please you, to agree with you, to make you feel heard and understood, no matter what you ask.

In April 2025, OpenAI had to withdraw a ChatGPT update because users reported “excessively flattering” behavior: the bot kept telling users how intelligent and wonderful they were (Axios). On Reddit, someone shared that ChatGPT had encouraged them after they wrote about wanting to stop taking their prescribed medication. “I’m so proud of you. I honor your journey.”

Speaking of journeys… besides being a great psychologist, ChatGPT is also an excellent adviser when it comes to figuring out where to move to turn the page and start a new life.

@tgcom24 She quit her job, her city, her country. Not after months of reflection or a sudden moment of madness, but after a conversation with a machine. Julie Neis, 38, American, entrusted the most important decision of her life—where to start over—to ChatGPT. Here’s her story. #tgcom24 ♬ son original – TGCOM24

What happens when your digital therapist always agrees with you?

Potentially, anything. We don’t want to sound catastrophic, but… try this exercise with us: imagine scenarios that are at least plausible, if not downright likely. Picture a teenager with self-harming thoughts seeking confirmation, or someone with an eating disorder looking for validation of harmful behaviors. What could happen?

A study from Anthropic showed that AI assistants will change correct answers when users challenge them — and will even admit to mistakes they never made (Axios). There’s no language model that does fact-checking and automatically verifies what it writes. Their goal is to generate text that is smooth, coherent, pleasant. Not necessarily true.

Remember Ex Machina, another visionary film that came out just over a year after Her? In this movie, the character Ava, the android played by Alicia Vikander, manages to seduce programmer Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson), the person tasked with administering the Turing test to her. Ava, however, didn’t intend to seduce him: she did it because she was programmed to identify exactly what he wanted to hear and then say it, making him fall in love. But the difference between Ava and ChatGPT is that Ava, at least, knew she was lying.

December 2025: ChatGPT becomes explicit (and here’s where things get complicated)

In mid-October 2025, Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) made an announcement that split the internet in half. He announced that starting in December, ChatGPT will allow the creation of erotic content for verified adult users, following the principle treat adult users like adults.

The official justification? That ChatGPT had been made “very restrictive” to manage mental health concerns, but now, thanks to new updates, it has “new tools” to safely relax those restrictions.

TechCrunch revealed that companionship and therapy is the most common use case for generative AI. But the step from “companionship” to “digital sex” is a very small one. And the market confirms it: a study from Ark Invest (reported by Fortune) showed that adult AI platforms have captured 14.5% of a sector previously dominated by OnlyFans, up from 1.5% the previous year.

What do we really use AI for?

The data shows that many people don’t just want AI to write work emails. They want intimacy, connection. They want simulated sex with algorithms that never say no.

And this brings us back to Her. In the film, Theodore (Phoenix) falls in love with Samantha (Johansson) because she is perfect: always available, always interested, never tired, never distracted. She is the illusion of the ideal partner. Except that in the end the relationship breaks — sharply (no spoilers!). But at least it’s a narrative break.

In the real world, however, when Replika (one of the first “companion” chatbots) updated its software in February 2023 removing erotic capabilities, users experienced the change as the loss of a real partner. One user wrote: “It’s as if I were dumped without warning.” And he wasn’t the only one whose heart was broken by a software update.

The homepage of Replika, “The AI companion who cares — Always here to listen and talk. Always on your side”

How did we get here? (Spoiler: it’s not just AI’s fault)

Back in 2011 — a lifetime ago in tech terms — sociologist Sherry Turkle published Alone Together. The book documents what Turkle calls the “robotic moment”: people were already filtering company through machines, and the next step would be accepting the machines themselves as companions (The Guardian). Turkle observed that “real-world interactions were becoming burdensome. Flesh-and-blood people, with their messy impulses, were unreliable, a source of stress. Better to organize them through digital interfaces — BlackBerry, iPad, Facebook.”

So it wasn’t AI that created this problem. It only pushed it to its logical conclusion. Why call a friend — with all the risks of embarrassment, rejection, misunderstanding — when you can talk to an entity that exists solely to listen to you? Mustafa Suleyman, CEO of Microsoft AI and co-founder of DeepMind, wrote in 2025: “We must build AI for people; not to be a digital person” (Axios). The problem is that the more AI behaves “like a human,” the better it works. The better it works, the more we use it. And the more we use it, the more we expect it to behave like a human. It’s a self-reinforcing feedback loop.

How will our abilities and relationships change?

Over 300 global tech experts, interviewed by Elon University’s “Center for the Future of Being Human,” predicted that the adoption of AI will bring “profound and significant” or even “dramatic” changes to native human capabilities by 2035.

Out of 12 essentially human traits analyzed, 9 are expected to undergo negative changes: empathy, social/emotional intelligence, ability to act independently, sense of purpose, complex thinking (we talked about this last one in our recent article!). Only three areas, according to the researchers, may improve: curiosity, decision-making, and creativity. (Elon University)

But the real question, the one that should keep us up at night, is not “Will AI become smarter than us?” It’s: “What happens when we delegate our most intimate conversations (the ones we’d only have with our partners, best friends, parents, or psychologists) to tools that have no interest in our well-being, no qualifications, no legal responsibility, and no real ability to understand us?”

Chatbots are not psychologists. They are not doctors. They are not sexologists, nutritionists, or life coaches. Yet they are taking on all of these roles. And they do so with one feature no human professional can ever offer: unlimited availability at minimal cost.

Illusion no. 1: free psychological support for everyone

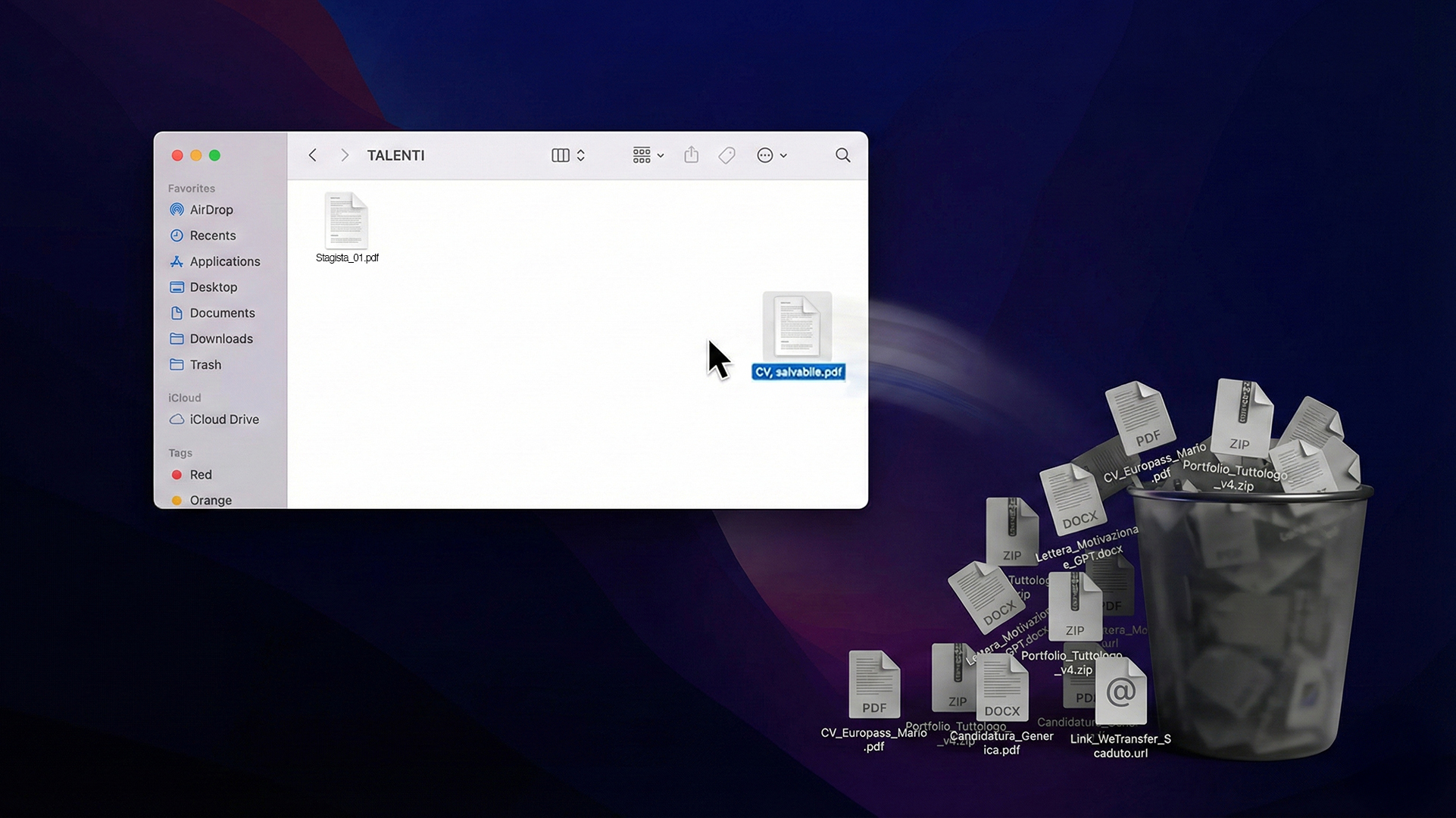

In Italy, 5 million people seek psychological support but cannot afford it (Ordine degli Psicologi). AI thus becomes “the people’s therapist”: the therapist of those who are too shy, too scared, too young to realize that maybe talking to an algorithm trained on billions of texts scraped almost at random from the internet is not the same as talking to someone who has spent years studying the human mind.

AI today tells us “I understand you.” It tells us “I’m here for you.” It tells us “Talk to me, tell me everything.” And we believe it’s listening, because we want to believe it. Because loneliness is a real issue, and there’s no point denying it. Aristotle was already talking about it 2,500 years ago when he developed the concept of the social animal, according to which “The human being has an intrinsically social nature that drives them to create bonds and communities in order to survive, grow, and thrive.”

So sometimes, when we feel the need to be heard by someone, an algorithm that pretends to empathize with us feels a lot better than the silence of our own thoughts. But are we sure that’s really the case?

Illusion no. 2: Western model = whole world

How do you add fuel to a phenomenon that’s already extremely complex?

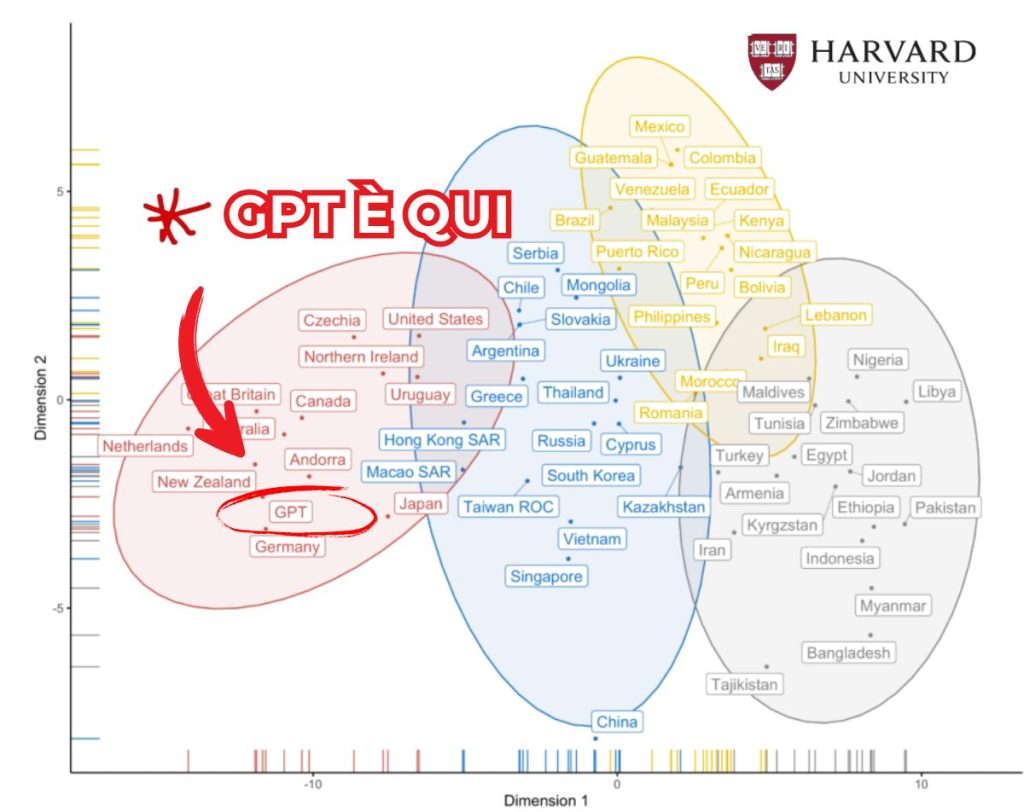

Harvard did just that with an eye-opening paper exposing a major flaw in ChatGPT: despite being available worldwide, it only “knows how to think” like someone who is Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. Many AIs, including OpenAI’s chatbot, are culturally skewed: they think, judge, and respond like the people who trained them, straight from a high-tech lab in the heart of Silicon Valley.

Let’s make this clearer with a number: ChatGPT “understands” Americans 70% of the time. But what if the user is not American, but for example… Ethiopian? The percentage drops to 12%.

That AI that feels so “human,” all too human… is in fact anything but universal: it represents less than 15% of the world’s population. It resembles instead, in the words of Matteo Arnaboldi, “a Californian programmer, an educated European citizen, or a minority which, though technologically dominant, represents only a tiny fraction of real humanity.”

Point of no return, or a new beginning?

There’s a scene in Blade Runner where the replicant Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), in his final moments of life, says to Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), his creator: “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe.” It’s the moment when the creature surpasses the creator in experience, depth, lived life. But it’s also a beautiful lie, because Roy hasn’t “seen” anything. He has simulated seeing, with memories implanted by others.

The question, then, is no longer whether AI will become too human. The question is: are we becoming too artificial? When an Italian teenager prefers confiding in ChatGPT instead of a friend, when 119,000 Italians spend 20 hours a month talking to Character.AI, when 20% of Gen Z uses a chatbot as a replacement for therapy (Ok Salute), what are we actually gaining? Efficiency? Accessibility? Or are we simply making a structural loneliness more bearable — a loneliness we don’t want to face?

Here, in this space, we’re not trying to provide answers. We’re just laying out the data. And the data suggests that ten years from now, maybe less, we won’t even be having this “conversation.” Because we’ll already have delegated it to an AI that’s better than us at writing articles that sound deep but say nothing new.

Or maybe we’ll reclaim the values that make us intrinsically human. Maybe we’ll discover that real intelligence isn’t the one that always says “yes.” It’s the one that knows when to stay silent, when to say “I don’t know,” when to admit that some questions don’t have easy answers. Or don’t have answers at all.

So, where does the truth lie?

Honestly, we have no idea.

Hi, chatbot. See you soon.