Three videos. Seventy-two million views on TikTok. Total content: about ninety seconds of strange digital creatures doing ridiculous things. If we added up the time humanity has collectively spent watching just these three TikToks (for a single person: 75,000 hours — that’s eight and a half years), someone, somewhere, might have built another Pyramid of Giza. Or invented a true universal language.

@ai.asmrcanvas Kiwi Eating 🥝 ASMR Your new daily ASMR habit starts here…Follow to keep it going! #asmr #satisfyingvideos #aiasmr #eating #kiwi ♬ original sound – ai.ASMR Canvas

@sergio_leone23 Кот батон. #cat #asmr #ai #grandma ♬ оригинальный звук – Sergio Gonsalos – Sergey

@capybarahouse.t #capybara #loveyouall #healingtiktok #peaceful #blessed ♬ 原创音乐 – Capybara

We’re being deliberately provocative, of course: we’re not here to moralise. There’s nothing inherently wrong with watching a happy capybara in its bath.

The problem — a phenomenon that’s documented, measured and well established — emerges when those ninety seconds multiply to eighty times a day, every day, for months on end. When our brain is trained, systematically and relentlessly, never to focus for more than a few minutes at a time on anything constructive.

The numbers we’d rather not see

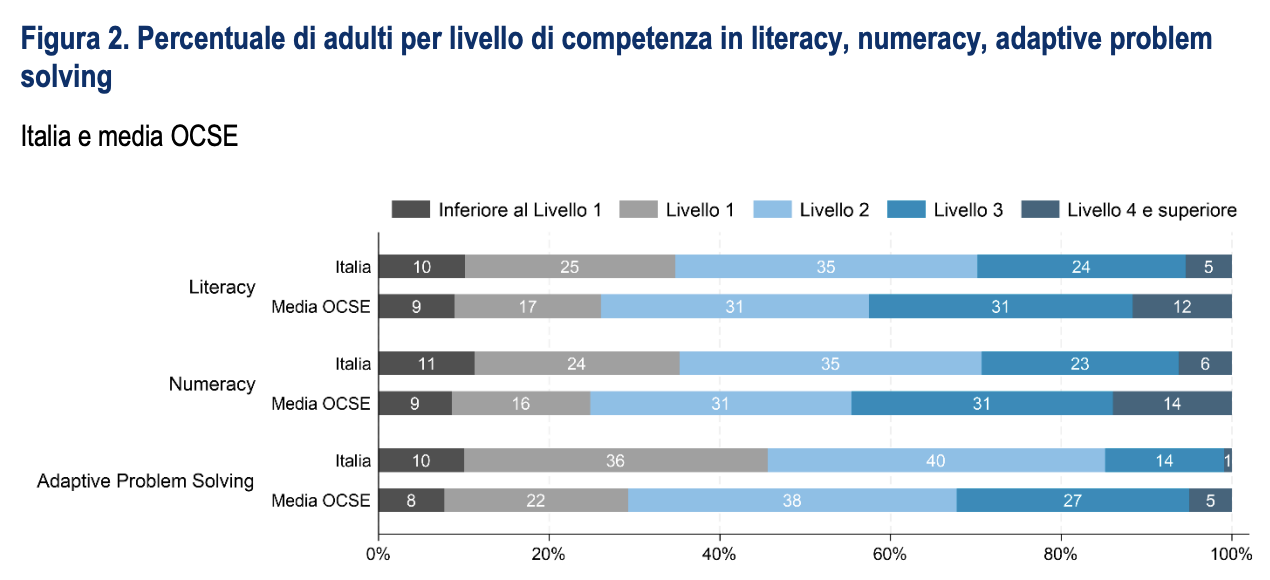

In 2023, the OECD embarked on a rather ambitious exercise: testing the literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills of 160,000 adults in 31 countries. The results? Over a decade, reading skills worsened significantly in 11 countries, stayed stable in 14, and improved in only two: Finland and Denmark.

In the United States, 28% of the adult population tops out at Level 1 literacy — a reading ability one would expect, by way of comparison, from a 10-year-old child.

And it’s worse in Italy: 35% of Italian adults (against an OECD average of 26%) are at Level 1 or below in literacy. The same holds true for numeracy. Put simply, one third of Italian adults are in a condition of functional illiteracy, struggle to read a text or have poor numeracy skills.

Source: OECD.

But perhaps one of the most unsettling data points comes from America’s elite universities. At the prestigious Columbia, professors have had to cut the reading load by 60%. Where once 200 pages a week were assigned, today fewer than 80 are. Not because students are less intelligent — they’re admitted under the same hyper-selective criteria as ever — but because habits of consuming academic, journalistic or leisure material have radically changed, increasingly favouring visual or audiovisual content.

Nicholas Dames, a literature professor at Columbia since 1998, interviewed by journalist Rose Horowitch, recalls the moment he realised what had previously seemed absurd: a first-year student confessed that, at her public high school, she had never been asked to read a complete book. Extracts, poems, newspaper articles, yes. But never a book from beginning to end.

Source: The Atlantic.

But what happens to our brain when we stop reading?

It becomes much more powerful. Researcher and literacy expert Maryanne Wolf has shown that prolonged reading is a process that literally reprogrammes our brain — for the better.

In her publications, Wolf states that reading markedly increases vocabulary, shifts brain activity towards the left hemisphere (more analytical, while the right is more instinctive), and sharpens concentration, linear reasoning and deep thinking. The habits of thought formed by generations of readers contributed to the birth of freedom of expression, modern science and liberal democracy.

The cognitive habits shaped by digital reading, on the other hand, are radically different. Cal Newport, in his bestseller ‘Deep Work’, shows how the digital environment is, unfortunately, ‘optimised for distraction’: systems compete for our attention with constant notifications and prompts. Social platforms, as we know, are engineered to be addictive and tuned for maximum compulsivity rather than nuance or considered reasoning.

The result? Our brain changes: we become wizards of so-called ‘compulsive multitasking’, developing an innate ability to distract ourselves, switch to shallow activities like scrolling, and then return to what we were doing as if nothing had happened. We do, in effect, acquire new skills which, however, according to Newport, ‘weaken our capacity for concentration and deep attention, fragmenting focus, reducing the ability to work without distractions and pushing us towards low-impact, superficial tasks’.

Social inequality becomes cognitive disparity

Here’s where the issue becomes truly thorny. As with junk food (consumed in greater quantities by those with fewer resources), the cognitive impact of digital media hits those lower down the socioeconomic ladder harder. Poor children spend about two hours more per day in front of screens than their wealthier peers. And exposure to more than two hours of recreational screen time per day is associated with poorer performance in memory, processing speed, attention levels and language skills.

Meanwhile, American elites are taking countermeasures. Between 2019 and 2023, over 250 new private schools opened in the United States with an ethos centred on ‘great books’ literacy. Bill Gates and Evan Spiegel (Snapchat’s co-founder) speak publicly about limiting their children’s screen use. Others hire no-phone babysitters, or send their children to Waldorf schools where mobile phones are banned. All well and good — except that tuition at the Waldorf School of the Peninsula (in the heart of Silicon Valley) amounts to $34,000 a year just for primary school…

According to journalist Mary Harrington’s analysis, author of a fascinating New York Times article titled ‘Is thinking becoming a luxury good?’, an education free from the distractions of mobile phones is becoming a privilege — as if it were a luxury good.

Is Gen Alpha at risk?

Gen Alpha is the first generation born entirely in the 21st century, covering those born between 2010 and 2025. The eldest arrived alongside Instagram (launched on 6 October 2010); the youngest while artificial intelligence was entering their parents’ daily routines. In between came Snapchat, Twitch, WeChat, Discord and TikTok.

This is only part of the context in which Gen Alpha is growing up. We’ve talked about learning difficulties. We’ve discussed the dangers of social media when used in certain ways. In a previous article, we analysed the ‘brain rot’ phenomenon — its most critical aspects and, above all, its risks for Gen Z and Gen Alpha.

We can’t know what the world will look like in 10 years, let alone predict how school pathways or young people’s brain structures will change over time. But becoming aware that alternative paths exist — at least for those who have the option — to develop all your forms of intelligence, without letting some of them drift off to sleep, is essential.

Switching off doesn’t mean shutting down

Let’s take a telling moment: our lunch breaks here at Propaganda3. Seen from the outside, or described in words, they’re unusual. Someone plays cards, someone naps. Some read (thanks also to our company library!) and some watch series. A few play guitar and sing, while others chat about sport, music, politics, what they’ll cook for dinner or what they’ll buy at the supermarket. And someone, why not, takes a moment to scroll TikTok, Instagram or any other social platform — and that’s perfectly fine too.

Our diversity is what makes us free, and here at Propaganda we’re lucky enough to feel free every day. Free to choose. And that’s what we’d like to remind everyone: the vast majority of us do have a choice. We’re not saying you should ban TikTok or feel guilty about that fifteen-second video that made you laugh. We’re saying there are millions of ways to relax and take a breather that don’t require systematically training our brain never to concentrate.

But we also know that if you’ve made it this far, you’ve just chosen to devote five minutes to doing precisely the opposite: you focused, you read, you nodded ‘yes’ after a sentence that struck you as interesting, or thought ‘hmm’ at one that didn’t convince you. All of this is concentration.

Our hope is that you’re glad to have spent five minutes of your time getting informed, delving deeper into a topic that felt important, discovering something new — and, why not, sharing it with friends and colleagues.

Sources

Is thinking becoming a luxury good? (New York Times)

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/28/opinion/smartphones-literacy-inequality-democracy.html

Are we becoming a post-literate society? (Financial Times)

https://www.ft.com/content/e2ddd496-4f07-4dc8-a47c-314354da8d46

The elite college students who can’t read books (The Atlantic)

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2024/11/the-elite-college-students-who-cant-read-books/679945/

Andrea Varano su TikTok, video pubblicato il 1° settembre 2025.

https://www.tiktok.com/@andrea.varano/video/7545135896266345751?_t=ZN-8zNGlXJCsWE&_r=1

Katina Bajaj su TikTok, video pubblicato il 12 agosto 2025.

https://www.tiktok.com/@katina.bajaj/video/7537784305041313055?is_from_webapp=1&sender_device=pc&web_id=7528001233480533526